A New Way of Seeing our Children’s Emotionally-Triggered Actions

Mis + Behavior

Here’s something with which all parents everywhere have to deal. Just for signing up as a parent, we’ll have to face this little concept. We’ll be asked to pick sides, to align ourselves with certain strategies, and to commit ourselves fully to waging all-out war. We’ll be told we have no choice. That anything else would be, well – permissiveness.

But we’ve made a huge imaginary Mis + Take…

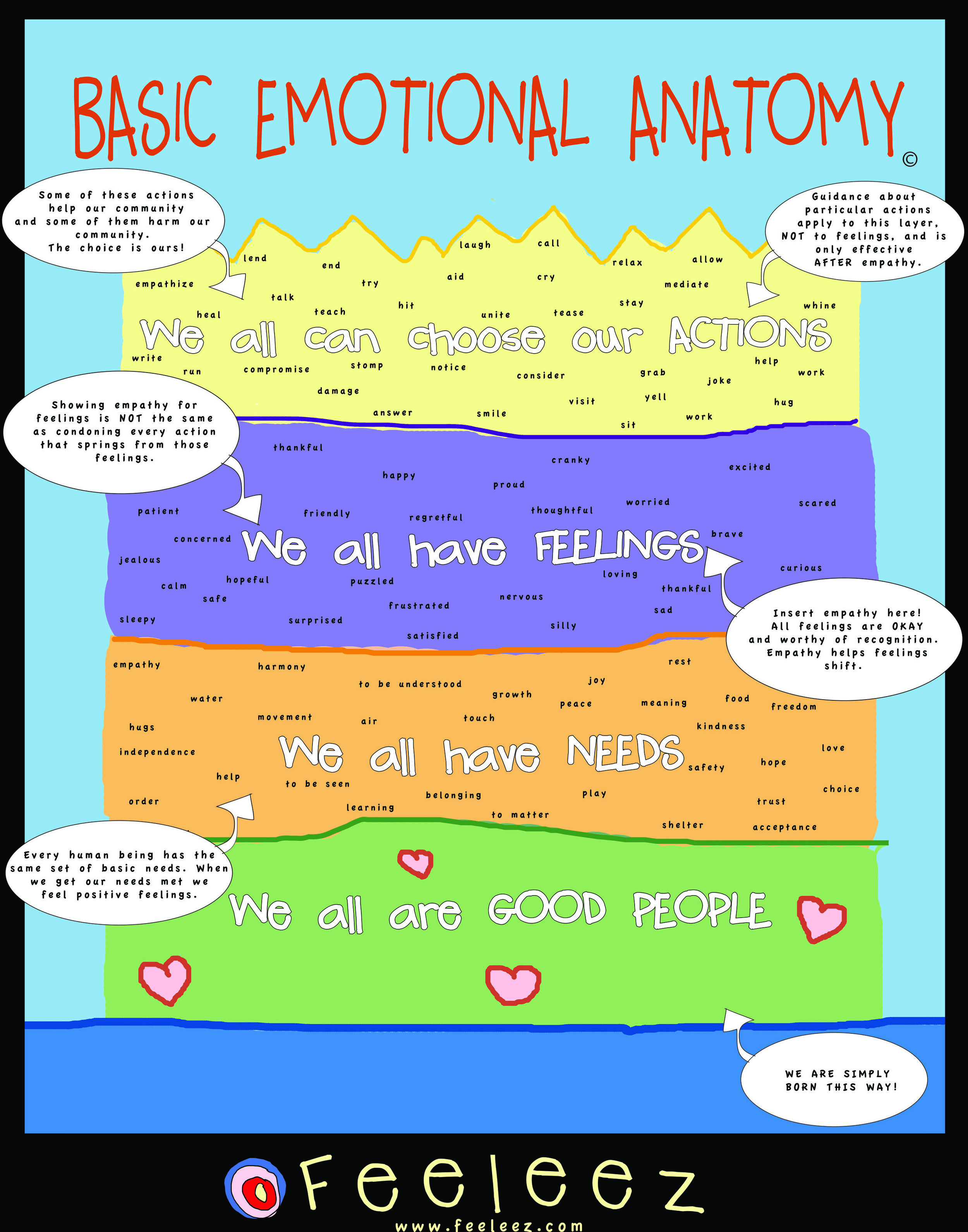

The word “misbehavior” means: “an improper, inappropriate, or bad manner of acting”, and of course this means in terms of social norms, family rules, etc.. In use, though, it’s commonly applied to any action that we grown-ups don’t like, and never fails to imply some nefarious intent on the part of the “misbehaver”. The truth is, however, that children (especially young ones) who are experiencing powerful emotions aren’t choosing actions -- they’re compelled by their feelings to act in ways that they can’t regulate. They aren’t misbehaving. They’re doing exactly as their biology intends. And whether we like it or not, it couldn’t be more appropriate for where they are developmentally and what they are experiencing physio-emotionally.

The Safety System or Ain’t Misbehavin’

When children experience intense emotion, they lose contact with the executive part of the brain. That means, just like someone with Alzheimer’s can’t access the brain machinery for memories, so too, an upset child can’t access the brain machinery for thinking clearly, or acting carefully. When emotion strikes, that emotion has to be dealt with first in order for the executive brain, which controls thinking and motor impulses (among a host of other higher functions), to come back online. This happens in one or more of three ways:

1. Like every healthy mammal, the child calls out for help and receives the empathetic support that she needs in order to let out the emotion, and/or get other needs met, and then returns to a calm state and higher-brain function.

2. The child’s nervous system obliges her body to some action to discharge the intensity of the uncomfortable feeling. Her brain is on it’s way to reverting to a survival state, and punching her sister is a tiny release, a minor, incremental improvement over the jealousy and powerlessness, etc., she was feeling just before.

3. The child stuffs the feeling and tries to move on, though encumbered more and more by accumulating, painful feelings; until 1. and/or 2. above happens.

What we’ve been trained to call “misbehavior” is actually a neural survival mechanism…

When our kids cry for help, it’s easier to see, but we’d do well to become skilled at recognizing the call for assistance in their disagreeable actions as well. Their brains are driving them to do something to which we’ll attend, so that they can get the emotional support they need in order to return to higher functionality. And what’s more -- they can’t stop it without our help because their impulse control is in the executive brain where they’ve lost access. It’s honestly unrealistic for us to expect that they’d be able to act in any other way! They’re doing exactly as is normal and best for the human brain. Period. And if we want to help them “act right” and “make good choices” then we have to help them get “back in their right minds”.

When children are behaving in ways that don’t fit in with the herd, it’s actually a very fortunate signal that there’s something wrong with how they feel. And if there’s something wrong with how they feel, it’s usually a sign that they have a need that is going unmet. So the next time your kid “acts up” you can thank him for being so clear with you!

Emotional Anatomy Chart from Feeleez

Working in Reverse

Fortunately, this system is a two-way street. We can have a massive effect on how our kids act simply by how we attend to their feelings and their needs.

When a child is engaged in an activity that we would normally call misbehavior, we have an enormous opportunity before us…

Instead of just punishing or guilt-tripping our way into smoldering, temporary compliance, we can turn this rift in the family joy into a boon for the relationship and invite our children to a whole range of other more agreeable types of actions, just by being with them in empathy. Here’s a few ideas to start:

1. Respond to the signal for help – recognizing that our children are being forced to “act up” and can’t “put on the breaks”; and recognizing their suffering and need for assistance.

2. Get curious – instead of trying to hammer in a lesson on etiquette (for which the higher brain is necessary to hear and remember), we can look under the surface of the behavior for the uncomfortable feeling(s) driving it; and find out if there is an(other) unmet need associated with it. Ask, “What’s going on for you, love? Are you upset?” and wait and listen. Remember that when we parents feel disrespected (or saddened, or enraged) by the behavior, that’s a good indication of what feeling it is discharging for the child, too.

3. Assist children with the feelings involved and struggling to get out – they need our help to let out those big emotions and calm down and “think straight” again. The shortest distance between our children’s disagreeable actions and ones we’d rather see is through the co-managed off-loading of their painful feelings. Be with them in empathy in whatever manner(s) they like best for solely the feelings piece. And wait.

4. Then if there is an(other) unmet need fueling the uncomfortable emotion, we can help meet that as well. Look for a need to meet in every action that annoys, and find a more agreeable way to meet it. We can almost always find ways to meet our children’s needs in a manner that works for us as well, but if for some reason we can’t, then it’s a clear indicator that our work right then lies in assisting with the feelings associated with that disappointment instead – remaining firm while focusing on being kind.

This process restores family peace, reaffirms the parent-child bond, and makes way for more ideal actions and better, higher-brain choices to follow. Every time.

Now, don’t get hung up on whether or not to “give in” to your child’s ill-conceived or worse controlled plans to have his or her needs met…

Assisting with feelings and meeting needs is separate from condoning actions. We can do all of the above, and then when they can hear us, still talk about what we’d prefer they do in the future. And because of how we’ve handled them, we’ve made it easier and more attractive for them to handle us with empathy, too. And when it comes right down to it, that’s all we hope to teach them about how to “behave” anyway! Once we translate “misbehavior” as “having feelings and trying to get needs met” then we can see, we don’t have to wage war on what they do, we just have to meet them where they are.

*

Be well.